I begin with some basics of story mechanics. Quite probably much of it will be familiar — feel free to skim if you feel like you’ve heard all of this before.

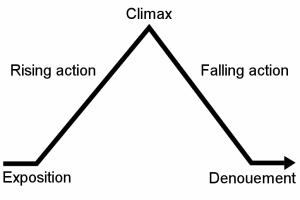

A basic part of a story is its arc. The arc, graphed out, is a roughly slanted triangle, with the slope on the lefthand side usually significantly longer. I’ve provided a diagram of it, also called Freytag’s pyramid, or sometimes his triangle.

The X axis of that diagram is story tension; the Y axis is the story over time. As the storyline progresses, while there may be momentary lulls or dips in tension, the movement is upward. Tension is increased by things like complications, reversals, and raising the stakes.

But more than that, something in the story must change. The problem must be resolved in some fashion, even if it’s only to show that there is no resolution. The change provides the resolution; without it, we have only a scene or static moment, which is generally an unsatisfying thing for a reader. Often (I might go so far as to say usually) there are two changes, an internal one inside the protagonist and the external one taking place around the protagonist.

The change can, in some circumstances, take place outside the story by occurring in the reader’s understanding of the story. What seems innocent (or vile) at the outset turns out to be the opposite. This sort of subtle change can be beautiful when it works. If you look at Rachel Swirsky’s “If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love“ for example, you can see this sort of shift at work as we learn more about the circumstances behind the story and move from light-hearted to deeply sad in a story whose emotional core is — for me at least — the power of fantasy as a temporary escape, but only a temporary one. This sort of change, taken as far as it can go, is a twist ending and is best suited to flash fiction, but it can and does work at greater length, as with Ian Banks’ The Wasp Factory (I don’t want to spoil the ending, but urge you to find the book and read it if you haven’t.)

Do you need to understand what will change before you begin to write the story? No. But some story origins will have signs and clues leading to the change, while others will require you step back and consider it in various ways before moving on.

There are multiple forms in which an idea for a story can present itself to a writer. What I’ve done is try to present each, along with examples drawn from my own and other authors’ writings, with some tips and tricks for expanding them into a complete story.

Ways into a story are separated into structures, fragments, and directives. I’ve split them into these groups for the purpose of talking about them more easily, but each group has similarities of approach and possible issues that may make it useful to, after finishing an overall group, spend some time thinking about the material and trying to apply it to one or more stories before moving on.

- Structures include plot, technique, stealing from other writers, culturally determined structure, and conceits/devices. These are the paint-by-numbers kits of the writing world, or at least they are ways to start a story that give you a great deal to work with.

- Fragments may yield considerably less information. They include characters, dialogue, setting, scene, beginning, ending, title, images, or objects.

- Directives give you little information but are more about the form in which you will shape the story: its flavor or flair, if you will. They include narrators, point of view, historical moments, concepts/issues, emotion, imitation or tribute, theme anthology, research, genre, and collaboration.

No matter what your starting point, at some point in the process of writing, you will need to think about the emotional core of your story, its heart. You can think of this as the “message” of the story overall, what it (not you) is trying to say about the art of being a self-aware, autonomous creature. That can vary, but examples are:

- Life is complicated

- You can’t always get what you want (but if you try real hard you can get what you need.)

- It’s important not to lie (or insert the ethic of your choice).

- Economics affects circumstances.

- Karma is a bitch.

- Etc.

You may not know this core going into the story, you may not know it in the middle of the writing or even at the very end. But before the story can be called finished, you need to figure it out.

The point at which you figure it out will affect your writing process. You may even use it as your starting point. I can only think of one time I’ve done this, which was the story “Elsewhere, Within, Elsewhen”, which I wrote for the anthology Beyond the Sun. I had been thinking about the idea that people accumulated grudges and slights and that sometimes those got in the way of communication and even healthy living. I took that idea and literalized the metaphor by creating creatures who consisted of such layers and turned out to have entirely different entities at their heart.

The point at which you realize the emotional core is the point at which it will begin helping you organize the story. It often happens to me that I do not reach the stage at which I think about this until after the first draft is done. In that case, this is part of the rewrite process, and involves my going back and reading the story in order to try to figure this out.

These are often the stories that are the most self-revelatory, because the moment we as author understand the message of a story, we begin constructing plausible deniability. Stories that are raw and full of emotion are rarely understood until after the fact of their construction, in my experience, unless you are deliberately sitting down to write about a painful experience in order to process and/or explore it.

Once you know the heart of a story, though, you know what to remove or add, because you can tell what’s getting in the way of the heart of things, and where it is not getting communicated sufficiently clearly.

A crucial point about this is that sometimes it can take time, and it’s very hard to force it. Usually you should let it steep a while. It’s my belief that your unconscious mind takes some time to turn it around and consider it from a few angles before delivering up something worthwhile. You can force it through focused timed writings, sitting down and just writing within constraints, but you will do a lot of thrashing around creating superfluous verbiage that you cannot use in the final version of the story.

Want more of this sort of thing? Check out The Rambo Academy for Wayward Writers.

I recently tweeted this: “

I recently tweeted this: “

22 Responses

I climbed Freytag’s Pyramid because it was there and needed climbing.

I climbed Freytag’s Pyramid and all I got was a lousy t-shirt.

This should be a tshirt on zazzle or cafepress. Also, I want to know what’s in the hidden chambers of Freytag’s Pyramid.

That WOULD make an awesome t-shirt.

RT @Catrambo: Class Excerpt: On Story Basics and Ways into Stories: https://t.co/5DH31W45lg

Gerard Houarner liked this on Facebook.

Matthew Masucci liked this on Facebook.

Jody Lynn Nye liked this on Facebook.

RT @Catrambo: Class Excerpt: On Story Basics and Ways into Stories: https://t.co/5DH31W45lg

Susan Kuonqui liked this on Facebook.

Michelle Young liked this on Facebook.

Andy Ainsworth liked this on Facebook.

On Story Basics and Ways Into Stories: https://t.co/8B9qxVp2yS

Class Excerpt: On Story Basics and Ways into Stories https://t.co/tOe3eypTzy

RT @Catrambo: On Story Basics and Ways Into Stories: https://t.co/8B9qxVp2yS

Stephanie Bissette-Roark liked this on Facebook.

RT @Catrambo: On Story Basics and Ways Into Stories: https://t.co/8B9qxVp2yS

RT @Catrambo: On Story Basics and Ways Into Stories: https://t.co/8B9qxVp2yS

On Story Basics and Ways into Stories – https://t.co/lLtRMzCMq8

One of the things I like about Sheri S Tepper’s novels is that the right-hand slope is incredibly steep. Three pages from the end, you’re still not sure of the outcome.

I hate those books where the plot or crisis gets resolved and then the author takes 50 pages or more to tie off all the loose ends.

Keep that slope good and steep please.