…only to be proven wrong, of course. A week or so ago at the Surrey International Writers Conference I was absolutely delighted when an audience member hit me with a new one that I hadn’t considered at all.

When I teach the class, which focuses on how to take an idea and use it to finish a story, I talk a little bit about story structure and writing process, but most of the class relies on asking participants what the idea is that they’re working with. This time, a woman said, “My idea is a twinned story” and explained that she wanted to write two stories in parallel.

You might argue that it’s a particular manifestation of a frame story, which is something covered in the Devices section of the class, but she wanted it to be more than that: her story was about a couple discovering letters in their attic that tell the story of another couple’s marriage. So let’s look at this according to the structure I use in Moving from Idea to Finished Draft, looking at what it is, what it gives you, what considerations you should take into account while writing, possible pitfalls, next steps, and a few exercises designed to increase understanding of the idea.

What It Is:

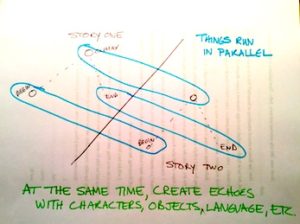

A twinned story holds two or more plots running in parallel to each other. The connection between them may be strong or more tenuous and faint, but it must exist. The stories should be distinct and are usually separated by location or time. Usually they are given roughly equal amounts of time in the story; one story may be stressed in importance over the other or they may be weighted equally.

However, I want to note that I am distinguishing this from a single storyline that takes place but is shown from multiple POVs; there are too many differences for that to get lumped in here.

What It Gives You:

The mirror structure actually gives you some very useful things. The first is that if you know the theme of one story, you know the theme of the other, because while it does not have to be an exact copy, it must reflect the other.

Similarly, the action of one story will be echoed in the other, and you may want to look for places where you can create echoes with objects, dialogue, actions, or other elements. If you know one story completely, you should be able to sketch out the other, but it is more likely that you will move back and forth between them, fleshing out elements as they appear in one story and need to be echoed in the other.

Considerations:

That connection between the plotlines is pretty crucial, or else the story will seem pointless and disjointed. It must be apparent to you as well as your reader.

Every time you switch from one plotline to another, you are bumping the reader out of the story and forcing their mental GPS to recalculate their route through it. Give them both the details and the time they need to re-orient themselves in the narrative. Remember that sensory stuff — particularly non-visual — is useful for pulling them back in.

Possible Pitfalls:

As with any device, there must be a reason to use this structure other than “it would be cool to write a twinned story.”

Remember as well that you must carry the plots out to satisfaction and that this will take space. The more plotlines you have the longer your piece will be, and you will need to resist the temptation to skimp for lack of room if you are trying to write to a particular word length.

Remember that you have less space than usual for everything as a result of this, including character development. Make everything count.

If you move about within time inside each of the storylines, providing flashbacks or memories for example, remember that you will need to make sure the reader does not mistake this for a movement to the other story line.

Next Steps:

- Take inventory of what you have. Where are the blank spots in both that you will need to address? What can each lend its partner?

- What are the differences between the story? Are there any you need to reconcile in order to make the parallels between them stronger?

- How will you mark the transitions between the two storylines?

- Map out the chronology of both storylines; you must know this in order to have them run in parallel.

Exercises:

- Figure out some differences between the main location for each story. If time is the difference, what has changed and what existed in the earlier landscape that is transformed or accommodated for in the later one? Along the same lines, if location is the difference and time is not, how is the time of year reflected differently in the two locations? Are there cultural aspects of society that change as well?

- Sketch out the main character(s) of each plotline and pair them with their alternate in the other story. List three differences and three similarities between them.

- Why are you using this device? List three things that you can do in one story that enhances the other one, such as having the same character appear in each in a way that deepens the reader’s understanding of them, showing how a landscape changes over time, or exploring the idea of inheritance.

In the class material, I try to provide an example of a story that came out of each kind of inspiration, but I don’t have one of these (how can this be?)! So I’m working on one, “The Sheriff Who Dreamed of Astronauts,” which Patreon supporters will get both early glimpses of and a first chance to read when it’s done, and that will get added to the class material at some point.

In the meantime, if you’d like to read interesting examples of this technique, I highly recommend Katherine Blake’s Interior Life for an innovative example, Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistlestop Cafe by Fannie Flagg for a traditional but highly satisfying example, and If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler by Italo Calvino for something that will really stretch you and make you think while (I hope) delighting you..

If you’d like some interesting audio talk about such things, here is Linda Aronson talking about parallel narratives (unlike me, she includes narratives of parallel characters):

And here is Quentin Tarratino talking about non-linear narrative in a way that may be useful:

We ended up granting a couple of deadline extensions for the novel workshop, and it seemed fairer to me to extend that to everyone. So if you are someone who wanted to apply and just didn’t get their stuff in order, you’re got an extra two weeks if you want to apply.

We ended up granting a couple of deadline extensions for the novel workshop, and it seemed fairer to me to extend that to everyone. So if you are someone who wanted to apply and just didn’t get their stuff in order, you’re got an extra two weeks if you want to apply.

34 Responses

For Writers: Working with Twinned and Twined Storylines: https://t.co/9B2zqfTZtI

RT @Catrambo: For Writers: Working with Twinned and Twined Storylines: https://t.co/9B2zqfTZtI

Danielle Myers Gembala liked this on Facebook.

David De Ryckere liked this on Facebook.

John McColley liked this on Facebook.

I LOVE TWINE.

HOW COULD YOU NOT?

http://www.theonion.com/graphic/war-on-string-may-be-unwinnable-says-cat-general-9636

THIS IS AWESOME.

Lia Keyes liked this on Facebook.

Jody Lynn Nye liked this on Facebook.

Tom Wright liked this on Facebook.

Robby Hilliard liked this on Facebook.

Love this post, Cat. Just what I needed.

Excellent!

Scott Gable liked this on Facebook.

Esther Hazleton liked this on Facebook.

Brianne Sorendo liked this on Facebook.

This morning’s post on writing parallel narratives: https://t.co/QPaIA6HHnu #amwriting

RT @Catrambo: This morning’s post on writing parallel narratives: https://t.co/QPaIA6HHnu #amwriting

RT @Catrambo: This morning’s post on writing parallel narratives: https://t.co/QPaIA6HHnu #amwriting

Thom Marrion liked this on Facebook.

Andy Dudak liked this on Facebook.

Jaime O. Mayer liked this on Facebook.

Trent Walters liked this on Facebook.

Yesterday’s post on writing parallel narratives: https://t.co/pK6hN0BFkQ

Shaoyan Hu liked this on Facebook.

Lynette M. Burrows liked this on Facebook.

Elyn Selu liked this on Facebook.

Elizabeth Bourne liked this on Facebook.

Randy Mac Kay liked this on Facebook.

Brenda Carr liked this on Facebook.

Thea Hutcheson liked this on Facebook.