Everyone says that indie publishing is the wave of the future. Avoiding gatekeepers, who are often prejudiced against particular ideas or demographics, and putting your work out there to see if it will sink or swim on its own, puts the power (and the money) back in the hands of the writers. I had an unusual idea and format that I realized would have difficulty finding a home because of its experimental nature, so I though I would give it a try.

Everyone says that indie publishing is the wave of the future. Avoiding gatekeepers, who are often prejudiced against particular ideas or demographics, and putting your work out there to see if it will sink or swim on its own, puts the power (and the money) back in the hands of the writers. I had an unusual idea and format that I realized would have difficulty finding a home because of its experimental nature, so I though I would give it a try.

Here’s the problem: It’s not free.

Amazon and others try to make you believe it’s free, but only if you want to give away a significant royalty chunk, and only if you don’t hire an editor (bad,) don’t hire a cover designer (worse,) don’t hire a formatter (fine if you have lots of time on your hands and are handy with computer programs; awful if not,) and don’t do any marketing or ever buy a copy to sell to your friends or at cons. If you do decide to go for it without any resources, people will dismiss your cover as tacky, your prose as terrible, and no one is ever going to see it in the sea of newly available titles anyway.

Not to mention there’s still the whiff of vanity publishing about it, so no matter how good you are, or how well you do, some people will never take you seriously.

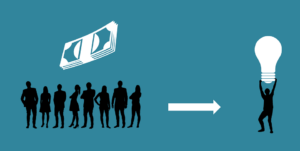

If you want to succeed at indie publishing, you have to be seen in the vast herd of new titles appearing every day. It takes money. That’s fine if you can afford it, but I found it daunting. So I asked myself, “How can I publish a book without defeating the purpose? How can I find capital that doesn’t eliminate my bottom line?”

I launched a Kickstarter to bring my Wyrd West stories to print. I budgeted for cover design, formatting, editing, marketing and stock purchase. And I asked my readers to contribute.

The response was better than I could have hoped. The Kickstarter was successful. The end result was a beautiful, professional book I had every right to be proud of, many of which were going directly to the readers that funded them.

But can this said to be truly self-published? I don’t think it can. This is a new way of doing things, in which readers choose to fund what they want to read. It puts the power directly in their hands. As it should be.

Even the backing of the Big 5 doesn’t guarantee a book’s success. It has to find an audience. It has to have resonance with the people who read it. Readers aren’t going to fund bad ideas, and if you’re a bad writer, they’re not going to support you more than once. So rather than being vetted by small groups of people on the top of a big pyramid of status and business acumen, Crowdpublished projects are vetted directly by the public.

As a writer, here’s a look at the differences I’ve found between being traditionally, independently, or Crowdpublished:

|

Traditional Publishing |

Indie Publishing |

Crowdpublishing |

|

|

Getting the Book Published in the First Place |

You may not be able to get a publisher interested. Chances are you will have a long wait. If you try something that’s too far outside of the mainstream in subject or presentation, don’t count on it. The publisher covers all publishing expenses and pays you a royalty. |

You can get the book published whenever you want. You are entirely responsible for expenses & getting people to read it. On the other hand, you get to keep a larger share of the royalty. |

If your audience will sustain your idea, you can publish the book whenever you want, and you know they, at least, will read it. Chances are they’ll get their friends to read it too, because they wouldn’t have invested if they didn’t think it was a good idea. If you’ve budgeted correctly, the expenses of printing some of your books, at any rate, will be covered. You receive indie royalties. |

|

Editing |

A professional editor who works for the publishing house will be provided to edit for you. Sometimes this leads to personality conflicts, but ultimately, it is the editor’s job to make your book into a marketable product, and that’s what they’re going to try to do. |

There are good editors and bad editors out there in the indie world, and you have to pay one. Some charge very good rates, others higher ones. Unless you’re dealing with a professional service with multiple editors, rate doesn’t necessarily indicate quality. However, most writers have no idea what makes a good editor, and it’s not just whether they can copyedit your spelling mistakes. A good editor will also be trying to make your book into a marketable product. That means they have to know what that looks like, and in my experience, the vast majority of indie editors haven’t a clue. |

You have all the innate disadvantages of indie editing, except that you can budget for that in your crowdfunder, so you can spring for the professional firm or someone you trust right away. |

|

Cover Design |

Your publisher decides on the cover, but will pay artists & designers to make it for you. |

You have the final say over the cover, but either you have to figure out Cover Design 101 or pay someone to do it well. |

You have the final say over the cover, but your readers cover the expense of creating it. |

|

Creative Control |

Your publisher has the final word on what will & will not go in the book. |

You have complete creative control. |

You have creative control ““ provided your readers will support your idea. |

|

Marketing & Promotion |

Your publisher expects you to do more of this than they used to, but they will still do a lot of it for you. They’ll market to bookstores and contact radio shows and podcasts. You will still be expected to use your own platform (especially online) to market, and you’ll probably still have to pay for your own book tour. They will decide much of how you and your book should be presented to the public. |

You are entirely responsible for the way you market yourself and your book. You’re also entirely responsible for the expenses. You probably don’t know as much about doing it as a professional publicist does, so there will be a lot of trial and error. Often, some of the places you’d like to promote to won’t talk to you because you don’t have a publisher’s clout. |

You still have many of the inherent problems of indie marketing. The exceptions are a) you are NOT entirely responsible for expenses (you can budget for that,) and b) a crowdfunding outlet is already a marketing platform. If you succeed at your goal, some shows who wouldn’t have talked to you as an indie will, because it’s a heartwarming success story and it’s apparent you do have an audience. |

I realize that Crowdpublishing is a bit like being PBS instead of MSNBC. You know that you have an audience. Although it might not be as easy for you to reach them as it is for corporations, that audience is dedicated enough to supporting your work that they are willing to ante up, sight-unseen. It’s “Funded in part by readers like you.”

It’s a godsend for SFF story markets. Many respected pro- and semi-pro markets use the Crowdpublishing model, including Clarkesworld, Uncanny, Strange Horizons, the entire EscapePod family, Third Flatiron, and more. And most SFF writers I know use the Crowdpublishing model, at least as far as setting up a Patreon, whether they’re just starting out or just shy of the New York Times bestseller list. I think this should be a point of pride.

I don’t believe that indie-publishing deserves its “lesser” reputation, because garbage gets published in all fields, and a big imprint is by no means a guarantee of quality. But I think when we’re asked if our project was self-published, we should smile and say, “No, it was Crowdpublished.” I think it’s a selling point.

I believe that any path a writer takes to success is a good one. Some people are really successful in the traditional or indie-publishing models, and regardless of which path they’ve taken, it’s hard. These are accomplishments worth taking pride in. But I think we should start thinking of Crowdpublishing as a third path within the literary market. There’s traditional publishing, and indie-publishing, and Crowdpublishing.

If you’re a writer who produces your own books, or a magazine editor, and you have a Kickstarter, GoFundMe or Patreon for the purpose, your work isn’t indie-published; it’s Crowdpublished. It’s not self-funded, or funded by shareholders; it’s funded by the public. And I think we should start talking about it that way.

Diane Morrison in an emerging neo-pro writer who just successfully ran a Kickstarter to publish her book, Once Upon a Time in the Wyrd West, available this month. She’s also appearing in Third Flatiron’s Terra! Tara! Terror!. This fall she will be offering a class through the Rambo Academy on finding time to write when you have none. Under her pen name Sable Aradia, she is a traditionally-published non-fiction author and blogger. She lives in Vernon, BC, Canada and she manages the SFWA YouTube channel. Right now, she’s doing a giveaway to support her Patreon membership drive. You can catch her on Twitter as @SableAradia, which means she’s not writing when she should be.

Enjoy this writing advice and want more content like it? Check out the classes Cat gives via the Rambo Academy for Wayward Writers, which offers both on-demand and live online writing classes for fantasy and science fiction writers from Cat and other authors, including Ann Leckie, Seanan McGuire, Fran Wilde and other talents! All classes include three free slots.

If you’re an author or other fantasy and science fiction creative, and want to do a guest blog post, please check out the guest blog post guidelines.