As mentioned in the Wall Street Journal (hello new readers coming from there!) last year, I came up with a new class, “Punk U: The Whys and Wherefores of Writing -punk Fiction“, which attempted to explore some of the -punk subgenres, starting with cyberpunk and progressing through steampunk, dieselpunk, nanopunk, solarpunk, afropunk, monkpunk, mannerpunk, and a dozen others. Of all of them, the most fascinating to me — and the one that’s had the greatest influence on my recent fiction, is hopepunk.

What is hopepunk? The term was first coined by Alexandra Rowland as the antithesis of “grimdark,” a speculative genre featuring fatalistic nihilism and a tooth vs. claw environment. She wrote:

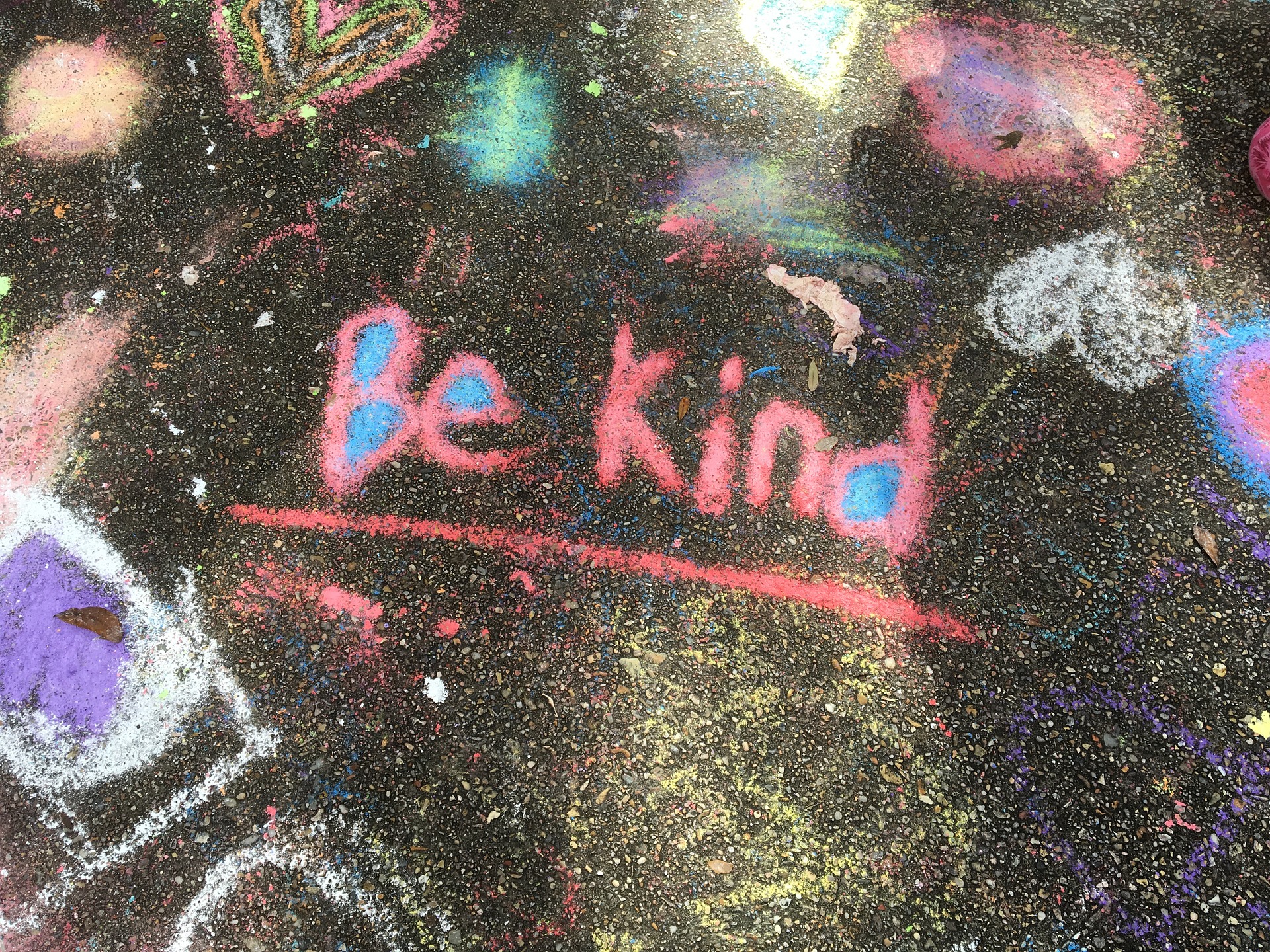

“The essence of grimdark is that everyone’s inherently sort of a bad person and does bad things, and that’s awful and disheartening and cynical. It’s looking at human nature and going, “˜The glass is half empty. “˜Hopepunk says, “˜No, I don’t accept that. Go fuck yourself: The glass is half full.’ Yeah, we’re all a messy mix of good and bad, flaws and virtues. We’ve all been mean and petty and cruel, but (and here’s the important part) we’ve also been soft and forgiving and kind. Hopepunk says that kindness and softness doesn’t equal weakness, and that in this world of brutal cynicism and nihilism, being kind is a political act. An act of rebellion.”

She wrote more about hopepunk in a follow-up essay, “One Atom of Justice, One Molecule of Mercy, and the Empire of Unsheathed Knives and expands on the idea of kindness as a political act further in this great essay:

Just the amount that I have seen people get more politically active in the last year has been amazing. I want to point out that kindness doesn’t necessarily mean softness. Kindness can mean standing up for someone who’s being bullied. If someone has a gun to your friend’s head, punching the guy with the gun is an act of kindness because you’re saving someone through that. So kindness is not always soft.

Kindness is not necessarily passive. Kindness is something that you can go out and fight for. Going to a protest, if you frame it in a particular way, is an act of kindness because you’re doing something for the future. You’re contributing to the future. You’re putting more good in the world is I think how I would define doing kindness. If you see someone being shouted at by a bigot on the subway, just standing up for them and having their back is an act of kindness.

And being kind also is something that requires so much bravery sometimes.

Others seized on the term with joyous abandon — and one of the signatures of hopepunk is, in my opinion, a sense that the writer is creating happily and full throttle. I’d call a number of the works on this year’s Nebula Award ballot hopepunk, particularly Trail of Lightning and The Calculating Stars, and I suspect there will be plenty of it on the Hugo and World Fantasy ballots this year as well.

Hopepunk is a reaction to our times, an insistence that a hollow world built of hatred and financial ambition is NOT the norm. It is stories of resistance, stories that celebrate friendship and truth and the things that make us human. In today’s world, being kind is one of the most radical things you can do, and you can see society trying to quash it by prosecuting those who offer food to the hungry, water to the thirsty, and shelter to those in need.

Claudie Arseneault spoke why she wanted hopepunk in her essay, Constructing a Kinder Future, for Strange Horizons:

The truth is, I’ve had enough of stories where your best friend or your closest family members are your most bitter enemies, where anyone you’re not in love with is an opponent to defeat, a potential traitor. Enough of stories where heroes must use each other as mere pawns, nothing more than pieces in a game, and abandon the “weak,” the naïve, the nice ones. Cruel ruthlessness is not our strength. It will not save us, and it should not be hailed as an acceptable means to an end, no matter the end. Our strength is in collaboration, in communities who link arms in the face of dangers, in perfect strangers donating to other people’s crowdfunding campaigns, and I want fiction to reflect that. I want characters who value their friends, who see perfect strangers as full-fledged human beings worthy of their help, and who fight the world with hope and kindness to be rewarded for it.

Is this desire for hope something new? No, it’s something that we’ve always celebrated in stories. Think about the moment in the Lord of the Rings when acts of kindness — first on Bilbo’s part, then on Frodo’s — lead to the moment where Gollum enables the ring’s destruction when Frodo falters and is on the brink of giving up his quest. Or go even further back, to Ovid’s Baucis and Philemon, who are rewarded for offering hospitality to strangers who turn out to be gods.

But in recent decades we’ve let other, darker stories, mocking the earnest and shredding empathy, supplant those fables. Stories written by the kleptocracy, designed to make its victims despair and give way to apathetic acceptance, stories spat out daily by the messageboard shitlords trying to convince us that meme-based mockery should be the first reaction to any appeal to the human heart. They’re there to enforce the rule that to step away from the line– to be joyous or non-conforming or outside the system in any way — is to be aberrant and wrong.

One of the things resisting that is hopepunk. The movement has caught on, with some perceiving it as vital to sowing the seeds of resistance, as with Vox describing it as “weaponized optimism”, adding “Hopepunk combines the aesthetics of choosing gentleness with the messy politics of revolution.” In an article for America, Jim McDermott went so far as to call it “quintessentially Catholic“, saying:

Death on the cross, understood not as some brutal cosmic math equation but a personal choice to continue to love and give and believe even when your life is at stake, is the beating heart of Catholic hopepunk. So is Jesus’s vision of the Kingdom of God as a banquet where all are welcome and called to kindness, and the lives of holy people like Martin Luther King, Jr., St. Francis of Assisi or Mary MacKillop, R.S.J., who refused to accept the premises of the reality in which they lived and experienced their own deaths and resurrections as a result. It’s Greg Boyle, S.J., insisting “There is no “˜them’ and “˜us,’ there is only us,” young people from all over the world traveling to Panama to create and imagine the church or Mary Oliver inviting us over and over in her poetry to consider “our one wild and precious life.”

Hopepunk is a movement that understands the importance of stories and how they can affect change, and so hopepunk often — perhaps even usually — has casts that are as diverse as the world around us, featuring characters of color, transexuals, a-romantics, differently-abled, and more, building empathy by showing that there are certain basic things any of us want, regardless of which other or others we do or don’t belong to.

In thinking about it, I find that hopepunk has crept into my life over the past few years. The Feminist Futures Storybundle I just curated holds more than one example, as did last year’s version of it. The anthology I edited last year, which appeared at the beginning of this month, If This Goes On, is full of examples of it.

Hopepunk led to me creating the class “Stories That Change Our World: Writing with Empathy, Insight, and Hope“. I spoke at length about the creation of the class in a recent essay for Clarkesworld magazine, but I could easily have titled the class, “The How-tos of Writing Hopepunk” and captured the same spirit.

One of the charms of the hopepunk definition is that it’s somewhat expandable — happy + hopeful, plus an insistence that it’s not a totally hostile universe, seems to be the base definition. In fact, it doesn’t have to be speculative fiction. Here’s Bryn Hammond talking about examples of it in historical fiction.

One of my favorite writers, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., often preached kindness in his work. He also said, “Be careful what you pretend to be, because you become it.” Try being kind, being mindful of your impact on the world and lives around you, and you may be surprised at exactly how kind you can be.

Recently hopepunk has elbowed its way into my writing as well, insisting on the importance of kindness and community. I just finished up a story where that instinct plays an important part, and I know that the next story I’m turning to, about animatronic Beatles in a post-apocalyptic landscape, will have many of the same resonances. Is this a deliberate focus or accidental? I’m not sure, but I feel hopeful about it.

HOPEPUNK READING LIST

Hopepunk novels:

Becky Chambers, The Wayfarers Series (starts with The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet)

Joyce Chng, Water Into Wine

Nicole Kimberling, Happy Snak

Mary Robinette Kowal, The Lady Astronaut series

Edward Lazelleri, The Guardians of Aandor Series

Marshall Ryan Maresca, The Way of the Shield and Shield of the People

Elizabeth McCoy, Queen of Roses

Tehlor Kay Mejia, We Set the Dark on Fire

Alexandra Rowland, A Conspiracy of Truths

R.J. Theodore, Flotsam

Carrie Vaughn, Bannerless

Hopepunk games:

Return to the Stars

Hopepunk novels coming out in 2019:

L.X. Beckett, Gamechanger

Aliette de Bodard, House of Sundering Flames

Bryan Camp, Gather the Fortunes.

A.J. Hackwith, The Library of the Unwritten

Tyler Hayes, The Imaginary Corpse

Leanna Renee Hieber, Miss Violet and the Great War

Marshall Ryan Maresca, A Parliament of Bodies

Alexandra Rowland, A Choir of Lies

Ferrett Steinmetz, Sol Majestic

Bogi Takács, The Trans Space Octopus Congregation

R.J. Theodore, Salvage

Patrick Tomlinson, Starship Repo

K.B. Wagers, Down Among the Dead

If you have suggestions for additions, please mail them to me or suggest them in the comments!

Notes and acknowledgments:

Thank you to Joyce Chng for pointing me towards the Arsenault essay.

How I Went From Writing 2000 Words a Day to 10000 Words a Day. When I started writing The Spirit War (Eli novel #4), I had a bit of a problem. I had a brand new baby and my life (like every new mother…

How I Went From Writing 2000 Words a Day to 10000 Words a Day. When I started writing The Spirit War (Eli novel #4), I had a bit of a problem. I had a brand new baby and my life (like every new mother…

8 Responses

I’ve got two – they may not be explicitly marketed as hopepunk, but I think they may fit.

Gate Crashers by Patrick Tomlinson. It’s funny, but it’s also thoughtful and the main characters do keep doing the right thing.

The Robots of Gotham by Todd McAulty. Yes, the AIs are in charge and the US is wracked by an invasion of AI governments, but I liked it because the main character kept on being decent to others.

Is there a difference between hopepunk and noblebright? It is nice to have a term to use shifts away from the cringey use of ‘noble’

Noblebright seems much more fantasy oriented somehow to me, if that makes sense? I’m right there with the cringiness of “noble,” it makes me think of smarmy unicorns.