As a writer, sometimes I find myself inspired to write by seeing other writers use a particular device and wondering what I can do with it. Having grown up with Star Trek and the Twilight Zone, and having encountered Babylon 5 in my teenage years, I felt confined by the typically anthropomorphic aliens, particularly the ones that were obvious stand-ins for Russians or Romans or other human cultures. The aliens were usually in supporting roles, and their biology, worldview and motivations were usually within human norms, not counting special abilities. I appreciated these characters and their stories, but I wondered how far writers could push the envelope in adopting an alien perspective. The Star Trek episode “Devil in the Dark” gave agency and purpose to a non-humanoid life form, and works like Lem’s Solaris, showed aliens that can be beyond alien understanding, but I wondered what stories could be told from non-human perspectives and how they could contribute to the genre.

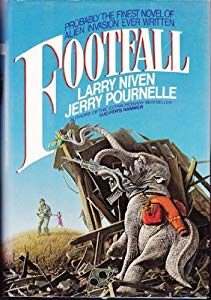

Footfall by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle gave me a more expansive sense of what could be accomplished by setting a story within a non-human perspective. The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. LeGuin and “Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang inspired me to consider reproduction and language that departed from the human norm. They drew me to non-human stories and came to enjoy stories that normalize aliens and de-normalize human experience,

Footfall by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle gave me a more expansive sense of what could be accomplished by setting a story within a non-human perspective. The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. LeGuin and “Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang inspired me to consider reproduction and language that departed from the human norm. They drew me to non-human stories and came to enjoy stories that normalize aliens and de-normalize human experience,

It is important to distinguish between stories that aim primarily to tell an alien story and those that use the alien as a prop in an allegory about human society. While the latter trope is common (“Eye of the Beholder” in Twilight Zone, “Let This Be Your Last Battlefield” in Star Trek, etc.), they can be too neatly prepackaged, so that the audience merely interprets the message, as explained by the human characters, rather than engaging in an alien experience.

Humans, at heart, are pattern detectors; the patterns of our daily lives inevitably become biases and prejudices. We can sometimes erode those prejudices by stepping outside of our usual experience and our usual metaphors for understanding the world (even the phrase “stepping outside” is grounded in human biology). Naturally, an alien world created by a human author will draw from human experience, but the characters’ thoughts and actions should be tangibly grounded in their own environment.

Like Plato leading prisoners out of his eponymous cave, a truly alien story, told within its own worldview, for its own sake, can expand the reader’s experience without framing or explaining the story in terms of a human cultural narrative.

I find that immersing myself in an alien culture without an easy allegory or a human narrative to explain the story can push me as a reader to be cognitively flexible and to understand others without necessarily expecting the experience to translate readily into their own.

So, what would I like to see more of from non-human characters in science fiction, and why? Here are a few ideas (for me, and for any other writers out there looking for a challenge). To show that I’m trying to practice what I preach, I’ll raise a few examples from my recently-completed #NaNoWriMo novel, Elevation, which is told in part from the perspective of an insectoid race.

Sensory systems: Non-humans in sci-fi almost invariably have the same senses as humans. If there is a sensory difference, it usually comes across as a one-off special ability. Other animals on Earth have sensory systems that differ multidimensionally across the senses. There are different color palettes, different ways of perceiving sound, and so on. Once an animal perceives something, it is classified and responded to in the context of its evolutionary history. One needs only consider the diversity of ways in which insects and birds, for instance, use sound and color, to appreciate what we will face when encountering extraterrestrial life. Even trained scientists can fail to appreciate ultraviolet light, infrared radiation, ultrasound, magnetic fields and other sensory cues. It also bears noting that different animals (and different humans) can perceive the same sensory information in different ways.

In my most recent novel project, Elevation, my characters communicate mainly through sound and smell. The use of smell means that ““ particularly in the cities ““ their social world is literally part of the atmosphere, shaping individual character interactions and cultural landscapes.

Communication: How many times do first contacts start with a simple message delivered through a straightforward audio message (such as “Take me to your leader”) without much thought into how the aliens perceive and use human language and how those words relate to their own concepts of the world. A Far Side comic strip parodies this by showing aliens with hand-shaped heads who – as it turns out – do not take kindly to a human attempt at a handshake. “Story of Your Life” explored non-linear communication (expressed well visually) in the movie Arrival), and it raises the question of how else alien communication could differ from our assumptions. How would an intelligent species use smell or touch to communicate?

In Elevation, the characters use their sense of smell to identify individuals socially. As a result, they do not, strictly speaking, have auditory or visual “names’ for each other, which poses a problem for humans trying to keep them straight. This has been a challenge for me when writing dialog and narration, but it compels me to think about the characters’ identities in new ways.

Agency and autonomy: It is important to me that the non-humans are more than talking points for the human characters’ debates. The characters should act in accordance with their own drives, in the contexts of their own worldview. This can be challenging as a writer because human readers will have moral expectations even of non-human characters. However, it is unreasonable to think that characters will act the way humans expect them to or strive toward human morality (which is hardly a monolithic construct anyway) unless led to do so by interaction with humans.

For example, the protagonist in Elevation has had children in the past, but ““ like some Earth insects ““ left the eggs behind after laying them and expresses no parental feeling toward them. Tending to young is driven by pheromones and is seen as a civic duty to the colony rather than a social bond. This is not framed as a statement on human parenting, but as an expression of the character’s drives in cultural context.

Reproduction: One of the primary drives (or the primary drive, depending on who you talk to) is reproduction. Whether or not we as individuals reproduce, our drives and our behavior are a product of the behaviors that led our ancestors to successfully reproduce (or else we would not be here). These behaviors, as they often are in humans, could be shrouded in social norms and mechanisms of social control, but these would be different from human norms.

For instance, in Elevation, the non-human characters reproduce parthenogenetically (through virgin birth) unless the eggs are fertilized by the King, the city’s sole male. Care for the fertilized eggs is done at hatcheries and nurseries near the Royal Palace, so care of larvae by individuals outside the city is seen either as putting on airs or as a desire to create a rival colony with a new king. These forces create social injustice and conflict, but in a way that differs from human conflicts.

In short, I like to explore non-human societies not to understand the human condition better, per se, but as a way of exploring the wider, underlying conditions that are a foundation not only for humanity but for intelligent life in a more general sense. It could be argued that science fiction and fantasy are meant for humans and, as such, that even the non-human characters will be seen through a human lens. I think there is truth to that, but I believe that the more clearly that an author can establish the worldview of all characters, the less vulnerable we are to literary solipsism, where are characters are simply preaching our own worldview back to us.

As we get into the habit ““ as readers and writers ““ of fleshing out alien characters in their own terms, perhaps we will be more vigilant in expecting the same from our human characters. Our concepts of normality, having been stretched by science fiction, might find themselves more capable of accepting the ways that we humans are alien to one another. It will encourage us, particularly in these tumultuous times, to move beyond simple allegories to examine the deeper underpinnings of our differences. I can’t say myself whether my work rises to that lofty ambition, but it is a goal well worth aiming for.

Works Cited

Chiang, T. (1998). “Story of your life.” Stories of your life and others,

117-78.

Larson, G. (2003).The Complete Far Side: 1980-1994. Andrews McMeel Pub.

Le Guin, U. K. (2012).The Left Hand of Darkness. Hachette UK.

Lem, S. (1970) Solaris. Walker & Co (US).

Niven, L., & Pournelle, J. (1985).Footfall. Del Rey.

Roddenberry, G. (1966). Star Trek. Desilu/Paramount

“Devil in the Dark” (1967) by Gene Coon and Gene Roddenberry.

“Let This Be Your Last Battlefield” (1969) by Oliver Crawford and Gene

Roddenberry.

Serling, S. Twilight Zone. (1956) CBS Productions.

“Eye of the Beholder” (1960) by Rod Serling.

Straczynski (1994). Babylon 5. Warner Brothers.

Author Bio: S. R. Algernon studied creative writing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has been published in Nature and Daily Science Fiction, and is the author of two short story anthologies, Walls and Wonders and Souls and Hallows. Both can be found at: https://sralgernon.wordpress.com/anthologies/. He currently resides in Michigan.

Author Bio: S. R. Algernon studied creative writing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has been published in Nature and Daily Science Fiction, and is the author of two short story anthologies, Walls and Wonders and Souls and Hallows. Both can be found at: https://sralgernon.wordpress.com/anthologies/. He currently resides in Michigan.

![Your brain is looking very, very closely at a brain.]](http://www.kittywumpus.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/neuron-300x188.jpg)