Rian Johnson’s superb Knives Out has stabbed its way into our hearts and minds. It’s not often that a screenplay so expertly crafted makes this kind of a splash. So, let’s use Knives Out to learn about MICEâ “”a handy approach to story focus and structure, incredibly useful for writers and re-writers. And as we go, we’ll use MICE to examine some aspects of Knives Out‘s intriguing construction.

The MICE Quotient, developed by Orson Scott Card, observes that there are different kinds of reader tension or investment in a story.[1] MICE suggests four typical kinds of reader investment that a story can court:

- Milieu: “Look, an interesting setting; let’s explore it!”

g. touring strange sights; immersion in a particular period or culture. - Idea: “Look, a perplexing question or concept to puzzle over!”

g. solving a mystery; following the consequences of an SF-nal premise. - Character: “Look, internal conflict!”

g. the hero overcoming their flaws, or questioning their role in life. - Event: “Look, external conflict!”

g. facing looming danger or a powerful foe; resolving a battle or a contest.

This is a rudimentary introduction to MICE’s elements, but in this piece, rudimentary is enough. Enough to understand that there is a selection of elements, of “kinds of tension” a writer can craft. With that, we’ll demonstrate MICE in action. We’ll see how to use MICE to interrogate a story, figuring out where its focus is, what kind of tension it’s building, and what makes it tick.

Knives Out, whose structure and focus are a fantastic mix of the conventional and the surprising, is the perfect case study. This piece assumes you’ve seen the film; spoilers ahoy![2]

Let’s Practice

Here’s our question: What kind of story is Knives Out?

Obviously, every story has many elements. But which feels most central? Is this story exploring a Milieu; investigating an Idea; following a Character’s development; or struggling against a threatening Event?

Seems easy enough: it’s a murder mystery. It begins by asking “Who killed Harlan Thrombey,” explores that question, and ends when it’s answered. The very model of an Idea focus.

But there’s something unusual going on; something more nuanced. The first act””let’s mark the first “act” as being everything up to the big twist””the first act, sure, is classic Idea. But that act ends with a vivid conclusion, revealing Marta as the tragic culprit.

And then we move into the second act. Where suddenly, we’re not following a murder investigation.

Instead, we’re following the ostensible murderer.

What kind of story does that give us?

Let’s see how we use MICE to answer that.

Identifying Focus

One way to tease a MICE focus out of a story is to ask what kind of buttons it’s pushing. What kind of promises is it making? What is it signaling as “the interesting part”?

For example, Act I, with its Idea focus, is all about questions. Not only the big question of who the murderer isâ “”it builds up lots of little questions that keep us curious. Who’s the stranger sitting in on witness interviews? Did all three of you show up at the same time? Who hired Benoit Blanc?

For example, Act I, with its Idea focus, is all about questions. Not only the big question of who the murderer isâ “”it builds up lots of little questions that keep us curious. Who’s the stranger sitting in on witness interviews? Did all three of you show up at the same time? Who hired Benoit Blanc?

Many of these little questions earn an immediate answer, which helps us feel we’re constantly discovering new and significant information.

But Act II isn’t about questions; not at all. It goes out of its way to avoid them. For example, Marta doesn’t care who is blackmailing her; only how she’ll get out of it. Likewise, “What’s in Harlan’s will?” has a startling answer””but the question is initially coached as a dull one, “a community theater performance of a tax return,” Blanc predicts. It’s the family bickering that looks like the interesting bit.

Act II doesn’t lack for critical clues towards the real murderer. But there’s not a single moment that’s framed as a discovery, as progress with the case, as a question being asked or answered.

All right, then. If Act II isn’t playing on our curiosity, what is it playing on? Let’s look at those same scenes and ask what is presented as the compelling part.

Where is our attention in the will-reading scene? It’s on the family’s intense, simmering animosity. How they all detest Ransom; how none of them can sit in the same room together. And then, when the will is revealed, all that anger and rage turns full force””on Marta.

Where is our attention in the will-reading scene? It’s on the family’s intense, simmering animosity. How they all detest Ransom; how none of them can sit in the same room together. And then, when the will is revealed, all that anger and rage turns full force””on Marta.

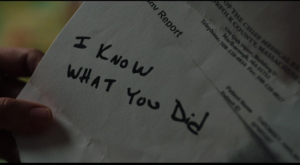

Where is our attention for the blackmail note? It arrives when Marta is beset on all sides; Walter’s threatened her mother and Blanc is looking for her. As soon as she and Ransom have read the note, we cut to the torched, smoking crime lab. This blackmailer is ruthless.

So the stress is on the danger to Marta, mounting higher and higher. Marta’s choice is to obey the instructions. Protecting herself is what’s important now, to Marta and to the story.

So the stress is on the danger to Marta, mounting higher and higher. Marta’s choice is to obey the instructions. Protecting herself is what’s important now, to Marta and to the story.

So we see that what drives Act II is threats, danger, uncertain outcomes. Will Marta be caught? Will she be exposed? Will she be bullied or guilted out of Harlan’s inheritance?

It’s an act full of external threats to Marta, and all the tension is on how they’re going to be resolved. That pegs Act II’s driving force as being Event.

Stark Separation

Most stories have multiple threads, of multiple MICE types””but usually, they’re intertwined, woven together. Knives Out does something different: it distinguishes between them, sometimes to startling extremes. One reason Knives Out makes a great case study is that it sets its Idea and Event threads cleanly side by side for comparison.

Act I was full of interrogations; questions being asked and answered. Act II introduces Ransom, in exactly the same situation. But this time, when the Lieutenant says, “We’d like to ask you a few questionsâ “””, Ransom blows right past him. Or, when Blanc thinks Greatnana has a piece of the puzzle, he doesn’t have any questions for her. He doesn’t know what to ask. He doesn’t have a line of inquiry. What a difference from Act I!

And you’ll find that threats, danger, uncertain outcomes””the bread and butter of an Event thread””are as absent from Act I as questions are absent from Act II. None of the tension is the “success or failure” variety; there is no moment of “I hope this works.” Act I offers no stakes, no consequences to finding the murderer or letting him escape; nothing beyond the promise of a complex, satisfying puzzle.

Even where you’d expect that a sense of danger would be absolutely necessary, it’s not there. Marta’s entire motive in following Harlan’s plan is the threat to her mother, yet she’s not the one who realizes it, who feels threatened. It’s Harlan who puts that together, while Marta gapes at him. That, right there, is the difference between “Marta’s mother could be deported” serving the story as an imminent threat, vs. as the answer to a question.

Even where you’d expect that a sense of danger would be absolutely necessary, it’s not there. Marta’s entire motive in following Harlan’s plan is the threat to her mother, yet she’s not the one who realizes it, who feels threatened. It’s Harlan who puts that together, while Marta gapes at him. That, right there, is the difference between “Marta’s mother could be deported” serving the story as an imminent threat, vs. as the answer to a question.

MICE as a Lens

Once you have a sense of your various MICE threads, you can use them to understand your own story better. Here are some questions MICE can help you ask and answer:

What’s my beginning? What’s my end? Each MICE type makes a different kind of promise to the reader. A thread begins when a promise is made, and ends when it’s paid off.

For an Idea story, the promise is a question; the payoff is its answer. Sure enough, Knives Out opens on a dead body, and ends with the culprit revealed. Even Act I, though, feels complete: it, too, ends with an answer, and a very definitive one. When Marta sees Harlan slitting his own throat, that’s the moment where the question has been firmly and completely answered””at least in Marta’s own mind.

For an Idea story, the promise is a question; the payoff is its answer. Sure enough, Knives Out opens on a dead body, and ends with the culprit revealed. Even Act I, though, feels complete: it, too, ends with an answer, and a very definitive one. When Marta sees Harlan slitting his own throat, that’s the moment where the question has been firmly and completely answered””at least in Marta’s own mind.

For an Event story, the promise is a situation of crisis; the payoff is how that crisis is resolved. Act II’s crisis is “Will Marta manage to avoid detection,” and that thread’s start is Marta trying, really really hard, to destroy the evidence without being caught. Where does it end? When we resolve the tension: when Marta stops trying; when she accepts defeat. When she decides to dial 911 rather than let Fran die, that’s Marta hitting her limit. Discovering that limit is the conclusion of this story thread.

For an Event story, the promise is a situation of crisis; the payoff is how that crisis is resolved. Act II’s crisis is “Will Marta manage to avoid detection,” and that thread’s start is Marta trying, really really hard, to destroy the evidence without being caught. Where does it end? When we resolve the tension: when Marta stops trying; when she accepts defeat. When she decides to dial 911 rather than let Fran die, that’s Marta hitting her limit. Discovering that limit is the conclusion of this story thread.

How do I increase tension? Each kind of tension needs to be handled, and heightened, in its own particular way.

An Idea thread’s focus is a fascinating puzzle. So, increase tension by demonstrating how interesting, complex, and rewarding the puzzle is. Knives Out plays up complexity by introducing a family full of lies and intrigue; and shows it Does Puzzles Good by asking, and then solving, some small ones along the way.

In an Event thread, the focus is external conflict. So here, demonstrate how dangerous and overwhelming the threat is, and tease any potential reward. Act II keeps showing us new ways that Marta’s in great danger, but also her realization that she might become safer than ever before.

How do I introduce something important? If you want readers to care about something new, it’s easiest to connect it to something they already care about.

In an Idea thread, that means being relevant to the driving question. The family members are interesting because they’re suspects. Some of Marta’s earliest introduction is as a living investigation aid; someone who knows all the secrets and can’t lie.

In an Event thread, anything that can make the conflict go better or worse is automatically interesting. Consider Ransom, who fans the flames of the family infighting, and then swoops in to save Marta from an immediate threat. We’re interested in him not for answers, but for how he affects Marta’s situation; as a mover and shaker in the Event thread.

Conclusion

We’ve seen the clearest structural threads in Knives Out. (If you’re curious for the rest, the film has Milieu and Character threads as well. Identifying those is an excellent exercise”¦)

Hopefully, I’ve demonstrated how to use MICE to find those threads, and gain insight into them.

Don’t think of MICE like a Sorting Hat, squeezing any story into four arbitrary boxes. Remember the goal we’ve seen here: understanding what makes your particular story tick; how your story pulls readers forward, and how it pays off its promises. MICE gives you a stepping-stone to those big questions””an easy question first, to get you in the right ballpark.

Usually, you can take it from there.

All screencaptures by KissThemGoodbye.Net.

[1] MICE is detailed in Card’s writing books, How To Write Science Fiction & Fantasy and Characters and Viewpoint.

Here is a good summary, hosted by The Gunn Center for the Study of Science Fiction.

[2] For reference, the full script, via Deadline.

BIO: Ziv Wities is a short-fiction evangelist, a devoted beta-reader, and an Assistant Editor at Diabolical Plots. If you enjoyed this piece, Ziv’s website collects a selection of writing Q&A and his expert overanalyses of Too Like The Lightning and Star Trek: Discovery. He tweets, vaguely, as @QuiteVague.

BIO: Ziv Wities is a short-fiction evangelist, a devoted beta-reader, and an Assistant Editor at Diabolical Plots. If you enjoyed this piece, Ziv’s website collects a selection of writing Q&A and his expert overanalyses of Too Like The Lightning and Star Trek: Discovery. He tweets, vaguely, as @QuiteVague.

If you’re an author or other fantasy and science fiction creative, and want to do a guest blog post, please check out the guest blog post guidelines. Or if you’re looking for community from other F&SF writers, sign up for the Rambo Academy for Wayward Writers Critclub!

One Response